Lithuania is a mostly rural country, sparsely populated with 2.8 million people (yet, the most populous of the three Baltics countries) with hundreds of tiny villages some only a handful of wood and stucco houses, perhaps a store or two, maybe a rail depot surrounded by sprawling crop lands, pine forests and lakes all criss-crossed by smooth 2-lane highways. Local bus stops are everywhere; there are no bill boards, no trash, occasional churches are visible. It feels safe and well kept. However, most people live in urban areas.

This country may seem small compared to other European countries like Spain or France but once here and making our way around it feels big. High speed modern clean trains zip across the country, countless long distance and local buses offer rural and urban riders convenient and frequent service across the Baltics and beyond to neighboring Poland, Russia and Belarus.

This is green farmland of crops, especially wheat, sugar beets, and potatoes, also butter, cheese, fish, milk. Scattered across the land can be seen rolled hay bales and large big-box warehouses of farm equipment. The main livestock products are beef and veal, chicken, lamb, pork.

Old wooden Czarist-style Russian houses punctuate the landscape along with ugly Soviet apartment blocks in larger towns. We saw a big sports stadium occasionally as we traveled by reliable bus services. The streets are clean and yards are tidy. Lithuania is part of the EU. In 2015 it adopted the euro currency making it the last of the three Baltic states to do so.

Read more.

I mention these pastoral descriptors as context for this story about LGBT life in this peaceful place. Here there is little aggression and hostility toward gays from the majority Lithuanian culture.

There are no overtly hostile gangs or religious police to strike at alleged misconduct. (Of course there are always unending political struggles about internal matters.) Homosexuality is not considered a serious domestic concern, which cuts both ways: gays are mostly left alone but legislated protections against discrimination are minimal, approved only as part of the criteria for European Union membership. Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1993, soon after the Soviet era ended. (photo left Trakai Castle)

In the hinterland, away from Vilnius and larger cities–such as Kaunas and Klaipėda–gay life is virtually non-existent or non-visible. As usual however, gay activists run into invisible and inaudible resistance from homophobic political and religious leaders and followers who resist equality and justice. Vestiges of anti-gay Soviet times are entrenched in the national psyche so support for same-sex partnerships and marriage is very low.

In the rural land scapes most farmers have no idea what gay life means other than a vague notion derived from church opinions (although 87% don’t attend) and from occasional TV characters. Young LGBT people usually move to big cities or out of the country.

LGBT Activity

Despite the low approval rate for gay life, Lithuania has the biggest and most active LGBT center in the Baltics, located in central Vilnius. “Lithuanian Gay League (LGL) is the only non-governmental organization in Lithuania, exclusively representing the interests of the local LGBT community. LGL is one of the most stable and mature organizations within the civic sector in the country, as it was founded on 3 December 1993. LGL maintains independence from any political or financial institutions with the goal of attaining effective social inclusion and integration of the local LGBT community into the larger Lithuania society. Based on its expertise in the fields of advocacy, awareness raising, community building, accumulated during twenty years of organizational existence, LGL strives for the consistent progress in and human rights for LGBT citizens.” (from their website)

I visited their home office on Pylimo Street, upstairs in a nondescript building with a modest sign on the door—LGL.

See: www.lgl.lt/en/?page_id=55 https://europa.eu/youth/volunteering/organisation/947117701_en. Also see; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithuanian_Gay_League

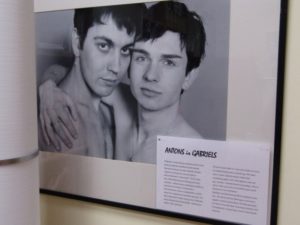

The office was a surprisingly large suite of office spaces, six rooms with staff and supplies for their numerous activities. There was a well-stocked library of books and pride literature swell as LGBT booklets, condoms, trans information, a Council of Europe reports, colorful Baltic Pride Parade programs for ‘equality days’, a report about bullying and a glossy hardcover picture book about Baltic Pride 1916. Interestingly there was also a booklet about “Queer history of Belarus in the Second Half of the 20th Century’. Hung on the walls were several photos of posed male and female couples in affectionate togetherness.

I was greeted by Tatiana, one of the EVS volunteers in the center. She was from Slovakia here for an unpaid 6-month internship sponsored by an home NGO. She was not gay but it didn’t matter; she wanted to participate in a human rights organization to prepare for a future in that field.

Tatiana introduced me to Egle, (photo left) the Communications Coordinator for LGL. Egle is also not gay; she was hired for her skills not her orientation. I had exchanged several e-mails with her to which she promptly replied. Although a woman of few words she was efficient and well organized especially keeping LGL’s website up to date with the latest news and

Tatiana introduced me to Egle, (photo left) the Communications Coordinator for LGL. Egle is also not gay; she was hired for her skills not her orientation. I had exchanged several e-mails with her to which she promptly replied. Although a woman of few words she was efficient and well organized especially keeping LGL’s website up to date with the latest news and  reports. She and Tatiana supplied me with documents, booklets and reports about recent projects and events, the most important of which was the Baltic Pride that happened earlier in the summer in Latvia. Baltic Pride rotates among the three Baltic countries yearly since 2013.

reports. She and Tatiana supplied me with documents, booklets and reports about recent projects and events, the most important of which was the Baltic Pride that happened earlier in the summer in Latvia. Baltic Pride rotates among the three Baltic countries yearly since 2013.

Tea and cookies were served as Vladimir (photo right) entered the room in a friendly bustle. We had only about 30 minutes to talk as he was packing for a well-deserved gay cruise with his partner Eduardas later that day. A handsome man of 42 with clear and focused blue eyes and short-cropped hair, he was very articulate in English (as was Egle), Estonian and Russian. Vladimir and Eduardas, were the co-founders of LGL, in 1993; Vladimir is current Executive Director of LGL, which is the most important advocate agency for LGBT rights in the country.

Getting down to business, I asked about a recent report on human rights in Europethat listed Lithuania last in ranking for human rights, equality, hate crimes, gender recognition, space in civil society and asylum. How was this possible with all the work that’s put into Lithuania’s society, especially by LGL.

One place to start is the recent approval by the Lithuania president Dalia Grybauskaite of an Equal Rights Opportunity Amendment that excludes ‘registered partners’ from the definition of ‘family’ to the labor laws. I asked him how is? His basic answer was “we were occupied by Russia for 46 years; they attempted to steal our identity and turn us into Soviet thinkers, which they did but not completely. As you can see Lithuania now has it’s identity back but there are a lot of leftover habits, including President Dalia’s homophobia”—another backward-looking leader still haunted by soviet ghosts.

To regain their individuality, Vladimir said, “if you believe in your cause you have to be patient and not be afraid,” so with much courage he and a small group of advocates and his life-partner Eduartus Platovas started LGL only two years after independence from the Soviet sphere. It was a  bold and daring effort, especially since many of Vladimir’s relatives live in Russia and were unprepared to change their attitudes towards homosexuality, which was illegal in Russia during the occupation years.

bold and daring effort, especially since many of Vladimir’s relatives live in Russia and were unprepared to change their attitudes towards homosexuality, which was illegal in Russia during the occupation years.

Vladimir’s and Eduartus’ coming out was very public, in 1995, sprawled across the front page of the local newspaper ‘Lithuanian Morning’ was this headline “Lithuanian gay couple lives every day as if on stage; they do not hide names in interview.” (Google translation.) They have been together for 26 years. After they were outed Vladimir, speaking for himself, said he was physically attacked, bitten on the arm, received hate mail and publicly denounced by his neighbors to the extent that now he only travels by taxi to work and to appointments. (photos right and left: LGL member couples in the office)

Nevertheless, “I’m glad I did it. It changed my life from passive to active as I was thrust into being an advocate, with Eduartus. “The European Union membership also demanded change of LGBT laws if we wanted to join.” So homosexuality was reluctantly decriminalized here in 1993 but that’s all. There are still no laws for protecting gays from discrimination or delineating their rights.

Needless to say the Catholic and Lutheran churches fought against the EU human rights and equality changes. Vladimir realizes what LGL is up against: “we can’t change them…their hate is entrenched, radical.” His modus is to move slowly and persistently. “The church is not overt in their opposition to us but works behind the scene to undermine any progress”. Vladimir told me about an incident in which the president was on his way to parliament to vote favorably for a change in certain human rights laws. On his way the president stopped to see the archbishop and by the time he left he had decided to change his vote to no.

The other great force that LGL works against is the ‘great bear’, Russia which is no friend of the LGBT population having recently passed repressive laws against any public display of LGBT advocacy, education or celebration in public. Lithuania is very close to Russia and many people speak Russian so there is a strong influence on media and TV broadcasting. “People here are afraid of Russia. They fear another invasion and takeover. Schools are afraid to change curricula that lean too far west. Each school district determines their own budget and teachers feel restrained from being too liberal. They don’t want to stand out.” That said, Vladimir said the younger generations are more courageous; as well, many also move abroad for education and work. (United States: 659,992 expat Lithuanians; Illinois 87,294; Pennsylvania 78,330; California 51,406 and others.)

And many return home after a time away bringing more modern and innovative ideas—sometimes too modern; he thought that Baltic Pride had recently taken on a ‘wild side’ in imitating Pride in western Europe and North America with their flamboyant floats, displays and riske´ costumes.

And many return home after a time away bringing more modern and innovative ideas—sometimes too modern; he thought that Baltic Pride had recently taken on a ‘wild side’ in imitating Pride in western Europe and North America with their flamboyant floats, displays and riske´ costumes.

Vladimir’s coming out and his advocacy work alienated him from his Russian relatives and he is not in much communication with them. Like most unthinking Russians the issue of homosexuality is shrouded in ignorance and fear and religious prejudice. But there is no going back only forward toward the liberation happening in the west of Europe and the Americas. As we spoke he said he and Eduartus were packing to go on a gay cruise. The trip was openly advertised in Lithuania and anyone was welcome to go. That simple act of packing a suitcase and boarding a ship focused on happy homosexuals establishes the two partners as generations beyond old and new Russia, beyond the myopic old world and the expansive new one. (photo left Vilnius Catholic Cathedral)

As for Egle, the highly competent not-gay assistant to Vladimir, she added that working for LGL has opened a new life for her that more meaningful and mature than the small village she came from. “Working with persecuted minorities has stimulated new ideas for me. I can see the struggle from inside the front lines and I see how hate and bigotry holds us back as a society. Bigotry cannot impede progress. It is unstoppable and I am glad to be a part of it… my family supports me completely in this.” Trans people who want to change gender cannot do it in Lithuania so England is the most liberal place to do that. It’s also permitted in Latvia and Estonia.

After my chat with Vladimir and Egle I met Virginija Prasmickaite (photo right) a Facebook-using lesbian grandmother on the staff of LGL. “I came out at 18 but it took two years to fully come out—it’s never really finished. But today it is much easier than ten years ago thanks to social media especially Facebook. She said she has never been bullied. She noted there are LGBT characters on Lithuanian cable TV, by streaming and in online media—but not in politics or in religion (at least, known). These are still the two big institutional opposition forces in the country. This, despite the more growing accepting attitudes in the general population and culture. There are also gay lyrics in music and music videos, she said.

Virginia said Vilnius is visibly changing despite the split between church and politics/police/military. The latter force has been forced to change over the past ten years by the non-discriminatory demands of the EU and the increasing popularity of Baltic Pride. In the early years police did little to protect marchers from right-wing assailants but with the legalization and acceptance of LGBT activities the police are now much more protectionist of LGBT Pride events here. The government doesn’t want to look bad in the eyes of neighbors.

Virginia said Vilnius is visibly changing despite the split between church and politics/police/military. The latter force has been forced to change over the past ten years by the non-discriminatory demands of the EU and the increasing popularity of Baltic Pride. In the early years police did little to protect marchers from right-wing assailants but with the legalization and acceptance of LGBT activities the police are now much more protectionist of LGBT Pride events here. The government doesn’t want to look bad in the eyes of neighbors.

As for public venues, Virginija said there is really only one club now in Vilnius, Soho. (http://www.sohoclub.lt/en/) Otherwise much of the community organizes around private parties and spontaneous events by means of social media.

One such event, while I was there, was the now annual LGBT film festival held each year at the Skalvija Theatre. (http://festivaliskreives.lt/en/) I went to opening night to see four indy films with themes of coming-out, being an immigrant and gay, being effeminately gay and feeling an outsider. The festival lasted a week. It was held without any police presence or opposition groups. The place was sold out and bubbled with enthusiastic friendship and acquaintance.

(The night before the film festival we went to the modernist Vilnius National Opera and Ballet Theatre (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithuanian_National_Opera_and_Ballet_Theatre), around the corner from Skalvija Theater, to see a performance of ‘Capulets and Montagues’ by Vincenzo Bellini.)

History of LGL

Shortly after its independence was restored, Lithuania decriminalized consensual sexual relations between men. Prior to this such relations were punishable by multi-year prison sentences. However, despite this progress, “Lithuanian homosexuals were still living underground, stigmatized by the media as HIV/AIDS spreaders,” Vladimir recalls. To combat such discrimination, he and Eduartus opened the Amsterdam club in Vilnius in 1993 and published the newspaper ‘Amsterd am’ in 1994. In April 1994, the two organized the first International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) East Europe conference, which took place in the Lithuanian town of Palanga. This event was the first conference of its kind in a post-Soviet state. The following year the two men started the Lithuanian Gay League in 1995, and the organization has since served as the only organization in the country exclusively fighting for the promotion of LGBT rights. (photo right: pro-gay rally at cathedral) (http://www.lgl.lt/en/)

am’ in 1994. In April 1994, the two organized the first International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) East Europe conference, which took place in the Lithuanian town of Palanga. This event was the first conference of its kind in a post-Soviet state. The following year the two men started the Lithuanian Gay League in 1995, and the organization has since served as the only organization in the country exclusively fighting for the promotion of LGBT rights. (photo right: pro-gay rally at cathedral) (http://www.lgl.lt/en/)

Functions of LGL

The key activities of the organization are (1) to help implement accepted international human rights for LGBT individuals in Lithuania; (2) prevent or weaken homophobic legislative initiatives at the same time to promote adoption of LGBT inclusive laws and policies; and (3) to oppose institutional discrimination against LGBT individuals. Of course, formal legal equality does not automatically translate into an improvement of quality of life. “Openness, a sense of communal belonging and identification of concrete goals represent the keys to success in the pursuit of LGBT equality in Lithuania.”

From their website: “LGL actively works in multiple fields affecting various aspects of LGBT lives in Lithuania. The right to freedom of expression is being protected through the challenging application of the Lithuanian ‘homosexual propaganda’ law through various legal avenues, developing awareness raising campaigns and supplementing public discourse with LGBT-related positive information. The right to freedom of peaceful assembly is being exercised through organizing large scale public awareness raising events, such as the annual Rainbow Days and the Baltic Pride festival which takes place once every three years (circulates yearly among the three Baltic states.” (see https://www.thedailybeast.com/baltic-pride-love-and-peace-always-wins).

As well, seminars, workshops and other cultural events for the local community are hosted. Opposing homophobic and transphobic hate crimes happens through monitoring and documenting hate motivated incidents, training law enforcement officials and raising awareness among the public to report witnessed or experienced hate crimes. “Finally, we offer advocacy on an international level through submitting reports to the international human rights protection mechanisms, issuing the organization’s newsletter (more than 6,000 international subscribers) and participating in the activities of the regional and European LGBT networks.” (photo left from Pinterest)

As well, seminars, workshops and other cultural events for the local community are hosted. Opposing homophobic and transphobic hate crimes happens through monitoring and documenting hate motivated incidents, training law enforcement officials and raising awareness among the public to report witnessed or experienced hate crimes. “Finally, we offer advocacy on an international level through submitting reports to the international human rights protection mechanisms, issuing the organization’s newsletter (more than 6,000 international subscribers) and participating in the activities of the regional and European LGBT networks.” (photo left from Pinterest)

Another Voice

Despite the recent statistics showing that most HIV cases now comprise straight drug users and not LGBT people, gays are still vulnerable, especially youth. Vladimir: “From my point of view if government keeps denying LGBT community existence (negative attitudes against LGBTs remain strong) those numbers will increase especially among younger people because they are reluctant to talk about it or go for an HIV test or talk to a doctor. Many young gays feel isolated and hide from public health help and often have unsafe sex because no one is talking openly about what they should avoid.”

Another example of entrenched homophobia, on 30th June, 2017 the national Inspector of Journalist Ethics in Lithuania, reached a decision on a complaint lodged by Eglė Kuktoraitė of LGL. The Inspector issued a warning against homophobic Faceboook poster, Laurynas Ragelskis from Vilnius, about his homophobic blog “get to know the skinhead faggots!” posted on his public Facebook page. It was determined that the content published was libelous, abusive, and degrading to the LGL Kuktoraitė’s honor and dignity. He was ordered not to repeat the offense or risk a strong fine.