By Richard Ammon

Updated July 2017

Also See:

Gay Ireland News & Reports 2000 to present

Gay Ireland Photo Galleries

Dublin’s Liberal Downtown

Dublin resonates with images and sounds both ancient and modern. As I walked into a gay/mixed café/bar called The Front Lounge, located only steps away from Dublin Castle, I could hear Christ Church Cathedral’s 18th century deep bell tolling six blocks away. Suddenly slicing through the sonorous chime like a jack hammer was the ramrod roar of a Kawasaki motorcycle charging past and round the corner of O’Neill’s Victorian pub with its stained-glass windows.

Inside the Front Lounge an assortment of patrons huddled over their Guinness, Cokes or Beaujolais chatting with friends as they gestured with cigaretted hands punctuating their talk. The Front Lounge is a gay/mixed place with high ceilings, (photo left) lots of floor space, comfortable sofas and a lunchtime food bar. Along the walls are paintings and sculptures bathed under display lighting.

(Unfortunately the Front Lounge closed in 2016 but I keep the story for its cultural value here.)

I listened for a while as four men in their twenties and thirties bantered and asserted their momentary thoughts about friendship, job security, a new outfit, changing flats, and gossip from a recent party. Each one of them had a cell phone that seemed to chirp every twelve minutes. From their accents it was obvious they were not all Irish. As it turned out no one in this little clutch was. One handsome dark man spoke Spanish. When I asked him from where he replied,”from Columbia—but my father is Irish”. Another member of their circle was from Brazil, a third from Paris and the other from Italy. Modern Dublin is busy, gay and very international.

I listened for a while as four men in their twenties and thirties bantered and asserted their momentary thoughts about friendship, job security, a new outfit, changing flats, and gossip from a recent party. Each one of them had a cell phone that seemed to chirp every twelve minutes. From their accents it was obvious they were not all Irish. As it turned out no one in this little clutch was. One handsome dark man spoke Spanish. When I asked him from where he replied,”from Columbia—but my father is Irish”. Another member of their circle was from Brazil, a third from Paris and the other from Italy. Modern Dublin is busy, gay and very international.

The capital is a remarkably comfortable metropolis in which to be a gay or lesbian denizen. In no small part is this due to the esteemed former President Mary Robinson (former UN high commissioner for Human Rights) who as a young solicitor took her own government to the European Court of Human Rights because of its anti-gay statutes still lingering on the books from an obsolete moral era.

She and co-counsel David Norris won their case and the Irish parliament was left struggling to modernize their legal thinking about homosexuality or face censure from the European Union, something Ireland could ill afford. In the ten years since that landmark action, Ireland has made up for lost time with some of the most pro-gay protections and equality laws in the European Union.

Literary Dublin

Dublin is also unique in the prominence and visibility it gives to its literary figures—gay or straight. James Joyce’s visage has at least two statues around town (photo right) .

.

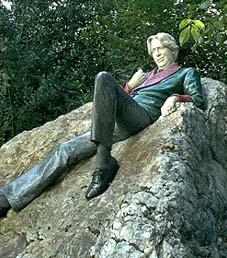

In Merrion Park, gay icon Oscar Wilde (once imprisoned for loving another man) has a dramatic—if not a quietly flamboyant–presence in colored marble. His unusual reclining statue (photo left in Merrion Square) is located across the street from his childhood home, now a museum owned by the American College in Dublin.

A nearby bo ok store sells postcards with the faces of Irish writers: in addition to the two well-knows with statues, there are J.M.Synge, Jonathan Swift, Sean O’Casey, Brendan Behan, W.B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, Bram Stoker, and George Bernard Shaw.

ok store sells postcards with the faces of Irish writers: in addition to the two well-knows with statues, there are J.M.Synge, Jonathan Swift, Sean O’Casey, Brendan Behan, W.B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, Bram Stoker, and George Bernard Shaw.

And this literary tradition is not just an historic artifact. In the October ’02 issue of Gi magazine (Gay Ireland) four of Ireland’s most respected living writers are profiled—all happen to be gay: Jamie O’Neill (author of ‘At Swim, Two Boys’, recently made into a mainstream film), Colm Toibin (nominated for the Booker Prize in 1999 for ‘The Blackwater Lightship’), Frank Ronan (awarded a top Irish prize for his 1989 ‘The Men Who Loved Evelyn Cotton’) and Keith Ridgway (debuted in 1989 with the intense ‘The Long Falling’).

So it should not be surprising that in such a literate town would be found a gay bar called The Wig & Pen, a “straight friendly” pub where writers bring their works-in-progress to read or listen to other budding literati.

Perhaps not as poetic or academic, ‘Gi’ magazine is a trendy glossy monthly with slick international fashion pics, gossip and images of celebrities as well as thoughtful interviews. There are serious features about dating, gay families, politics, gay immigrants as well as adverts for more mainstream items as cars, liquor and watches. There are no sex ads in the back. For those, one has to read GCN (Gay Community News), the monthly newspaper which has here-and-now entertainment, news and events. The third gay rag is Free! which are strictly gay-scene happenings at the various clubs, bars along with party gossip.

Gay Dublin at Night

As well as being a vibrant colorful museum with traffic coursing among its antique Georgian (18c) architecture, Dublin buzzes with countless cafes and pubs, some with daunting names like ‘The Bleeding Horse’. Focused in (but not limited to) a section of the old downtown called Temple Bar is Dublin’s modest but vital gay night life. Half a dozen bars/pubs, two, B&B’s, a couple of saunas, four or five disco clubs and dozens of organizations abide quietly among the trendy non-gay cafes, department stores, crystal shops, the ubiquitous Spar convenience stores, souvenir stalls—and hundreds of straight pubs populated with serious Irish drinkers (beer/lager is drunk here in pint-sized glasses).

The best-known gay bar is The George. It’s not unlike other watering holes in its casual ambience,  somewhat cliquish attitude and pricey drinks. Actually there are two Georges, one next to the other. The larger one has a late-night DJ spinning out disco tunes for the younger set as they shimmy on the dance floor. Some nights are film night and patrons watch flicks with gay themes: ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ was on when we stopped in. The other George one is half as big and serves up drinks to patrons twice the age without the dance.

somewhat cliquish attitude and pricey drinks. Actually there are two Georges, one next to the other. The larger one has a late-night DJ spinning out disco tunes for the younger set as they shimmy on the dance floor. Some nights are film night and patrons watch flicks with gay themes: ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ was on when we stopped in. The other George one is half as big and serves up drinks to patrons twice the age without the dance.

Just across the river on one of the main streets is Panti Bar a spacious popular bar on two floors. More than a gay brew house this venue also offers live programs such as dance performances and stand-up comedy night. (photo left)

What makes these watering holes and dance halls additionally appealing is they are not exiled to seamier edges of town among warehouses or run-down apartment blocks. Rather, they are close in next to chic restaurants, fashion boutiques and countless non-gay pubs.

What makes these watering holes and dance halls additionally appealing is they are not exiled to seamier edges of town among warehouses or run-down apartment blocks. Rather, they are close in next to chic restaurants, fashion boutiques and countless non-gay pubs.

But neither are there rainbow flags to signal their presence either. Except for the handsomer-than-usual bouncer at the entry to George there are no distinguishing markings to set it off. It’s an appropriate decision, much like similar decisions in other European cities where homosexuality—despite its legality—is still a volatile and ambivalent stimulus to roughneck hets who love their beer more than queers. Gay bashing is rare but neither is it absent from the street scene, especially after midnight and a few pints of brew.

A few blocks away—in opposite directions—are the two openly gay B&B’s. Inn on the Liffey looks out onto the Liffey River, in the center of the old town. There is also Frankie’s Guesthouse which has been offering its hospitality for nearly fifteen years. Tucked away on tiny Camden Place, it appears from the street as a colorful row house with lavender paint and hanging flowerpots. It offers 14 rooms to visitors some with and some without bath. TJ Cunningham (Joe) and his partner Frankie from Malaysia own the residence. For the literate-minded, it is only a couple of blocks from the birthplace of George Bernard Shaw. Frankie’s gets poor ratings on the hospitality scale.

Add to these venues the hip-hop light and sound that emanates from the numerous clubs (on different nights) such as Club Soho which has theme nights such as Candy, Campus (students) and Atomic (80’s night). On Sunday nights a “homosocialite merry-go-round” happens at the Spy Club. Then there is another nightclub called  Delicious at the Viva with its Red Room (“chill to mellow music”) and Blue Room (“camp classics and cocktails”). At the Temple Bar Music Center there is the monthly Club Tease with on-stage visuals (girth to drag), dance floor and two bars. Oil Can Harry’s pub and restaurant has food, live music and karaoke. There are currently two saunas for men in Dublin, the most popular one being aptly called the Boilerhouse.

Delicious at the Viva with its Red Room (“chill to mellow music”) and Blue Room (“camp classics and cocktails”). At the Temple Bar Music Center there is the monthly Club Tease with on-stage visuals (girth to drag), dance floor and two bars. Oil Can Harry’s pub and restaurant has food, live music and karaoke. There are currently two saunas for men in Dublin, the most popular one being aptly called the Boilerhouse.

And certainly not to be overlooked is the Alternative Miss Ireland pageant where, as I was told, “anything goes” from outrageous drag entries to coifed poodles. Billing itself as “the years most post-culturally-kinky event”, contestant vie in outlandish attire for the top prize. Check out their web site: (http://www.alternativemissireland.com/2002/index.asp?page=p review).

Heart of the Scene

The noisy and sexy gay scene may be found in the various bars and clubs, but the heart of the gay pulse in Dublin is found in the many quiet organizations that have formed over the past decade. All of these listings are found in ‘Free!’ and ‘GCN’, both published in Dublin. On the last page of GCN, I counted nearly 75 lesbigay listings of organizations and services offered in Dublin alone. This is clearly not a provincial city.

The range of special interest groups in Dublin is typical of a large urban gay community: sports, recovery, Amnesty International, bisexuals, naturists, leather, spiritual, parents, books/literary. Some of my favorites as I read the listings were Swimmin’ Wimmin and one called Clitoratae Sexualities (“sex, desire, gender, workshops, multimedia dance clubs, queer artists”—for women obviously).

Dublin’s most outstanding organization is easily the LGBT center called OUThouse whose administrator, Jim Lowther, told me there are approximately 18 groups that utilize the three stories of their recently purchased building on Capel Street in the downtown area. Their web site lists services and happenings that range from a drop-in café, a library-in-progress, counseling, telephone hotline, youth groups, a transsexual-support group as well as LGBT education outreach to the public.

Dublin’s most outstanding organization is easily the LGBT center called OUThouse whose administrator, Jim Lowther, told me there are approximately 18 groups that utilize the three stories of their recently purchased building on Capel Street in the downtown area. Their web site lists services and happenings that range from a drop-in café, a library-in-progress, counseling, telephone hotline, youth groups, a transsexual-support group as well as LGBT education outreach to the public.

Housed in one of the OUThouse offices is the highly valued Gay Men’s Health Project/Gay Health Network offering a variety of services and referrals for all health matters for the LGBT community. They also offer clinical services for STDs and HIV patients in association with Baggot Hospital.

Jim was especially proud that OUThouse is the only major LGBT center that actually owns their building, thanks in part to private donations and funding from the city of Dublin.. To cap this happy purchase, the President of Ireland, May McAlysse, attended the grand opening of the new quarters in 2002.

Lowther observed that much of the success of the center was due to a conscious effort to include lesbians and gay men equally in governance and offered services. “Exclusionary organizations, for men or women, often break down after an initial period of defiant excitement. So from the start we were sure to be inclusive in our efforts and it has worked very well here.” As well, OUThouse makes every effort to network closely with other LGBT organizations around the country including The Other Place in Cork city, Red Ribbon Health Project in Limerick, Foyle Friend in Derry (Northern Ireland) and the Rainbow Project in Derry and Belfast.

I asked Jim about gay activism in Ireland and how well it was organized.

“Homosexuality has only been decriminalized since 1993. Before that time there was considerable activity to change the laws; there was a big and constant push against that oppression. But once the law was changed there was a significant drop in activity. Many people thought that was all we needed, but in truth that’s just the beginning. Small town Irish thinking has not yet been liberated to the point where sexual varietion is acceptable.That’s why most gay people move to Dublin, to get away from small towns—and small thinking.

“Homosexuality has only been decriminalized since 1993. Before that time there was considerable activity to change the laws; there was a big and constant push against that oppression. But once the law was changed there was a significant drop in activity. Many people thought that was all we needed, but in truth that’s just the beginning. Small town Irish thinking has not yet been liberated to the point where sexual varietion is acceptable.That’s why most gay people move to Dublin, to get away from small towns—and small thinking.

“It’s slowly changing as people are exposed more with TV and films and more coverage in the media. You find some organizations in other cities like Cork, Limerick, Galway, Waterford and even less in some other towns like Kerry or Sligo. But there isn’t nearly the force or presence here of funded national organizations like Stonewall in England or the Human Rights Campaign in USA. Ireland is still a conservative country. There is still a lot of personal fear in coming out and risking rejection from your family or the community you live in.”

Is there any good news in any of this, I asked?

“At the local level, there are a lot of organizations to be praised, considering we’ve had less than ten years of legitimate life. Surprisingly, the best news comes from the federal government and not just from the changes in legislation. There is an Equality Authority which just this year issued a significant report on the status and condition of gays and lesbians and transsexuals in Ireland. It’s an extensive analysis based on consultations with many groups regarding important aspects of life and how they affect gays. It makes positive recommendations about marriage, adoption, arts support, discrimination, health, finance and education as they relate to the LGBT community. It’s very well done.”

However, Lowther continued, the challenge is to disseminate and activate this valuable information at the grass roots level. “It’s great to have this report but now the challenge is to inform rural gay people about their rights and to educate straight people about the unfair treatment of gays. It’s an effort we’re working on, however slowly.” One small step, he noted, was at a recent choral concert given by the police where they invited a gay choral group to sing with them. This is a small but big step. It came about because of an open minded police commissioner following a gay bashing and the resulting demand for remedial action.

However, Lowther continued, the challenge is to disseminate and activate this valuable information at the grass roots level. “It’s great to have this report but now the challenge is to inform rural gay people about their rights and to educate straight people about the unfair treatment of gays. It’s an effort we’re working on, however slowly.” One small step, he noted, was at a recent choral concert given by the police where they invited a gay choral group to sing with them. This is a small but big step. It came about because of an open minded police commissioner following a gay bashing and the resulting demand for remedial action.

Lowther also noted that right-wing fundamentalism in Ireland is rare and is confined to fringe groups for the most part. Physical violence against gays is rare. This comment reassured me a bit especially; earlier in the day as I was checking e-mail in a Dublin Internet café I overheard some obviously non-gay surfers, four guys in their young twenties, react with “that’s sick” when they came across a site about ex-ex gays. Irish prejudice is ever present even in ‘liberated’ Dublin.

Update from Passport magazine

Perhaps the most surprising change in the EU-era Dublin is the exuberance of the gay and lesbian community. Just a decade ago, the conservative Catholic church still held sway; now, non-discrimination laws are on the books and their spirit is embraced by a young, liberal population. Bertie Ahern, the (former) popular Taoiseach or Prime Minister of Ireland, recently re-opened The Outhouse (105 Capel Street), the LGBT community center in Dublin, and took the opportunity to forcefully promise civil partnership status for gay and lesbian couples.

While boasting nowhere near the volume of venues in meccas like New York or London, Dublin’s gay nightlife has diversified with this new openness. The appealing George barwith its deceptively large floor and clutter-free décor, (33-34 Parliament Street) consistently attracts a sophisticated after-work crowd, then packs in even more hip young men and women for its Tuesday night karaoke party.

In residence at the impressive Georgian Powerscourt Townhouse Centre (also well worth a stop for a shopping excursion during the daylight hours), Spice invites revelers to take a turn through various sitting rooms and multiple DJ-driven styles.

The biggest news on the scene, however, has to be the exceptional new companion club to The George, cheekily named The Dragon Bar (64-65 South Great Georges Street). Red-eyed gargoyles peer down from vaulted, blue-light-flooded ceilings while a very attractive mixed crowd lounges in velvet warrens and along multi-leveled bars; it’s gay night at Dracula’s Castle. Although the décor could easily slip over the edge into theme park, the Dragon stays clear of the precipice and serves up a relaxed, modern atmosphere with just enough of a self-aware wink. For the latest events, including the popular but irregularly scheduled women’s night, Kiss, check out the bulletin board at the Outhouse or the comprehensive listings in GCN magazine.

Going out doesn’t have to mean just hitting the bars, though; there are plenty of cultural options in this city that has always been known for its creativity. To sample the full range of Dublin’s contemporary arts scene, check out the Project Arts Centre (39 East Essex Street). Dance, theatre, visual art, and music jostle for attention in multiple galleries and performance spaces, all under one roof.

Just around the corner, the Irish Film Institute (6 Eustace Street) is dedicated to preserving the best of Ireland’s impressive film making heritage and to promoting up-and-coming celluloid talents. Monthly screenings, one-of-a-kind discussions, and special events open up their fascinating archives to visitors. If art house cinema feels a bit highbrow, just step outside into the public spaces of Temple Bar and experience Ireland’s longest and largest festival of free outdoor events, Diversions Festival 2008 (information available at the Temple Bar Cultural Centre, 12 East Essex Street). During the festival’s run from June to August, markets, music, and movies spill into the streets throughout the heart of Dublin. To get up-to-the-minute listings of even more galleries, museums, and events, click over to Dublin Tourism’s detailed website.

For all the talk of a new, worldly Ireland, it is worth remembering that Dublin has been the center of fashion before; the sights of the late eighteenth-century city can compete with even the most stylish of current trends. Imposing museums and stately Georgian homes, including the fascinating Number Twenty Nine (29 Fitzwilliam Street Lower), line the streets around Merrion Square. A stroll through the park, with its evocative collection of gas lamps and twisting, tree-shaded paths, is the perfect romantic escape, culminating in a visit to a statue of Dublin’s own Oscar Wilde. Colorful and sarcastic, fashionable and gay, he seems to be looking out at the city he left behind with a sly grin, reveling in the fact that Dublin has caught up to him at last.