Compiled by Richard Ammon

GlobalGayz.com

March 2012

Introduction

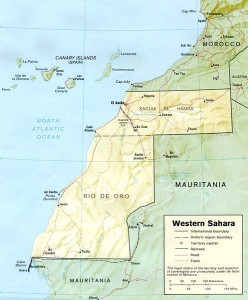

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) is a partially recognised state that claims sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony. On Feb. 27, 1976, the Polisario Front formally proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic and set up a government in exile, initiating a guerrilla war between the Polisario and Morocco, which continued until a 1991 cease-fire.

As part of the peace accords, a referendum was to be held among indigenous people, giving them the option between independence or inclusion to Morocco. However, to date the referendum has not been held because of questions over who is eligible to vote.

LGBT People in the SADR

There is virtually nothing to be found on the internet about LGBT people of Western Sahara. But given the fact that Muslims make up nearly 100% of the population of the area the usual high rejection and condemnation of homosexuality can readily be anticipated.

In Morocco, Mauritania and Algeria, which wholly surround WS, both male and female same-sex sexual activity are illegal so it can be assumed the same is true for all of Western Sahara even though there may be no officially legislated policy.

The Penal Code of Morocco criminalizes “lewd or unnatural acts with an individual of the same sex.”. Officially, same-sex sexual activity is illegal in Morocco and can be punished with anything from 6 months to 3 years imprisonment and a fine of 120 to 1200 dirams, However, the law is sporadically enforced by the authorities, with a degree of tolerance extended to homosexuality in the holiday resorts like Marrakesh.

Often such contact is a form of prostitution, involving tourists being approached by young Moroccan men. The status of LGBT people stems largely from traditional Islamic morality, which views homosexuality and cross dressing as signs of immorality. In contrast, the informal and private situation of LGBT activity differs from the official rule. Same-sex behavior is common among young unmarried Moroccan male friends as part of their maturation process. As well, countless European men migrate to Morocco for the ‘easy sex’, either for a holiday or seeking a more permanent relationship.

(See GlobalGayz.com Morocco stories)

Mauritania shares the longest border with WS. Shari’a law applies in Mauritania. According to the penal code from 1983 any adult Muslim caught engaging in an “unnatural act” with a member of the same sex is punishable with the death sentence by public stoning. In the past 15 years there has been no case of execution in the international media.

In Algeria, the laws regarding same-sex sexual activity read “Anyone guilty of a homosexual act (“outrage to public decency”) is punishable with imprisonment of between 2 months and two years, and with a fine of 500 to 2000 Algerian Dinars. If one of the participants is below 18 years old, the punishment for the older person can be raised to 3 years’ imprisonment and a fine of 10,000 dinars”. The Constitution stipulates that Islam shall be the official religion.

The criminal laws and prevailing social mores are used to justify vigilante honor killings. LGBT people are often abused and beaten up by family, neighbors or even members of the Algerian police. There is also the right to privacy that is guaranteed in Article 39 of the constitution. But as of 2011, no civil rights laws exists to prohibit unfair discrimination or harassment on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity in Algeria.

Country Description

The SADR government today controls about 20-25% of the territory it claims. It calls the territories under its control the Liberated Territories or the Free Zone. Morocco controls and administers the rest of the disputed territory and calls these lands its Southern Provinces. The SADR government considers the Moroccan-held territory occupied territory, while Morocco considers the much smaller SADR held territory to be a buffer zone.

The creation of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic was announced in Bir Lehlou in Western Sahara on February 27, 1976, as the Polisario declared the need for a new entity to fill what they considered a political void left by the departing Spanish colonisers. Bir Lehlou remained in Polisario-held territory under the 1991 cease-fire (see Settlement Plan) and has remained the government in exile’s symbolic capital of the exiled republic, while Polisario continues to claim the Moroccan held city of El Aaiún, as the capital of a would-be independent Western Sahara. Day-to-day business, however, is conducted in the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, which house most of the Sahrawi exile community.

In 1982, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) admitted the SADR as a member, acknowledging its status as the sovereign government of the Western Sahara. Over the years, more than 80 countries have recognized the SADR’s sovereignty – including Mexico and South Africa – although some suspended that recognition in the late 1990s and early 21st century.

Despite the SADR’s high levels of participation and organization, many question whether the Western Sahara would be a viable state. Arguments against the SADR’s readiness include its unproven abilities at taxation and the large territory it would have to administer, relative to a small population and limited resources. Nonetheless, the Saharawis have proven their capacity to administer three branches of government, an army, and five refugee camps, and have been perfecting their parliamentary democracy over the past three and a half decades. The Saharawis insist that if given the chance, they would create the first fully-democratic country in North Africa.

On 27 February 2011, the 35th anniversary of the proclamation of SADR was held in Tifariti, Western Sahara. Delegations, including parliamentarians, ambassadors, NGOs and activists from many countries participated in this event.

Human Rights Problems in SADR

Against Morocco

In October, 2006, a secret report by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees leaked to the media by the Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara detailing the deteriorating condition of human rights in the occupied territory of Western Sahara. The report details several eyewitness testimonies regarding violence associated with the Independence Intifada, particularly of the Moroccan police against peaceful demonstrators.

In March, 2010, the Sahrawi human rights activist Rachid Sghir was beaten by Moroccan policemen after an interview with the BBC.

On 28 August 2010, Moroccan police arrested 11 Spanish activists, who were demonstrating for independence for the disputed territory in El Aaiun (largest city in Western Sahara territory; population about 200,000). They claimed that the police had beat them, releasing a photo of one of the wounded.

In October, thousands of Sahrawis fled from El Aaiun and other towns to the outskirts of Lemseid oasis (Gdeim Izik), raising up an encampament of thousands of tents called the “Dignity camp”, in the biggest Sahrawi mobilization since the Spanish retreat in 1976. They protested against the discrimination of Sahrawis in labor and for the spoliation of the natural resources of Western Sahara by Morocco. The camp was surrounded by troops of the Moroccan Army and policemen, who blocked the supply of water, food and medicines to the camp.

Against Polisario Front

The most severe accusations of human rights abuses by the Polisario Front have been about the detention, killing and the abusive treatment of Moroccan prisoners of war from the late 70s to 2006. Other accusations were that some of the population are kept in the Tindouf refugee camps against their will and did not enjoy freedom of expression. Moroccan newspapers have aired reports of demonstrations being suppressed violently by POLISARIO forces in the Tindouf camps but these reports have not been confirmed by international media or human rights organizations.

Several international and Spanish human rights and aid organizations are active in the camps on a permanent basis, and dispute the Moroccan allegations; there are several people and organizations that claim the Tindouf camps are a model for running refugee camps democratically.

The Polisario Front released the last 404 POWs on 18 August 2005. About 1500 Moroccan soldier had been captured in the war

In April 2010, the Sahrawi government called on the UN to supervise Human rights in the “liberated territories” (territory under Polisario control) and refugee camps, hoping that Morocco would do the same.

As for refugees displaced by the war, in 2005 the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants[125] stated: “The Algerian Government allowed the rebel group, Polisario, to confine nearly a hundred thousand refugees from the disputed Western Sahara to four camps in desolate areas outside Tindouf military zone near the Moroccan border ‘for political and military, rather than humanitarian, reasons,’ according to one observer. According to Amnesty International, “This group of refugees does not enjoy the right to freedom of movement in Algeria. […] Those refugees who manage to leave the refugee camps without being authorized to do so are often arrested by the Algerian military and returned to the Polisario authorities, with whom they cooperate closely on matters of security.’ Polisario checkpoints surrounded the camps, the Algerian military guarded entry into Tindouf, and police operated checkpoints throughout the country.”

According to a 1998 report by War Resisters International, “during the guerrilla war” – i.e. between 1975 and 1991 – “POLISARIO recruitment formed an integral part of the education programme. At the age of 12, children were either integrated into the “National School of 12 October” which prepares the political and military cadres, or they have been sent abroad to Algeria, Cuba and Libya to receive military training as well as regular schooling. At conscription age (17) they returned from abroad to be incorporated into POLISARIO’s armed forces. They received more specialised training in engineering, radio, artillery, mechanics and desert warfare. At nineteen they became combatants.”