Introduction

A visit to Uzbekistan is a lesson in retrograde human rights policies. The level of respect for freedom of press and expression is very low. The country is politically a police state filled with the usual paranoia, repression, corruption and strong-arm enforcement of socialist ideologies that bring more suffering to people than progress. Needless to say, the LGBT community in Uzbekistan is virtually non-existent as an organization even for health care purposes. The infamous jailing of an author of a HIV prevention brochure in 2010 caused outrage from human rights activists. His crime was to mention same sex activity in his educational brochure. It will be a long time before “Gay Life in Uzbekistan” and human rights take their rightful place in national policies in Uzbekistan.

Compiled by Richard Ammon

GlobalGayz.com

March 2012

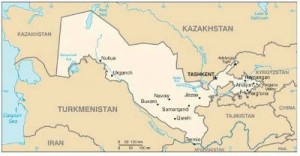

Country Description

Decades of questionable Soviet policies in pursuit of greater cotton production have resulted in a catastrophic scenario. The agricultural industry appears to be the main contributor to the pollution and devastation of the air and water in the country.

The Aral Sea disaster is a classic example. The Aral Sea used to be the fourth-largest inland sea on Earth, acting as an influencing factor in the air moisture. Since the 1960s, when the misuse of the Aral Sea water began, it has shrunk to less than 50% of its former area and decreased in volume threefold.

On October 27, 1924 the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic was created. On August 31, 1991, Uzbekistan declared independence, marking September 1 as a national holiday.

The country is now the world’s third largest exporter of cotton, and it is developing its mineral and petroleum reserves.

As for human rights, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch as well as US Department of State and the Council of the European Union define Uzbekistan as “an authoritarian state with limited civil rights” and express profound concern about “wide-scale violation of virtually all basic human rights”.

According to the reports, the most widespread violations are torture, arbitrary arrests, and various restrictions of freedoms: of religion, of speech and press, of free association and assembly. The reports maintain that the violations are most often committed against members of religious organizations, independent journalists, human rights activists and political activists, including members of the banned opposition parties.

Needless to say, gays right advocates are one of the most targeted populations in this rough country.

Treatment of Homosexuals by Society and by Government Authorities

Enclosed here are three reports that describe and analyze the situation of LGBT people in Uzbekistan.

(1)

Harsh Jail Time for Uzbek AIDS Activist

Dictatorship says brochure on same-sex relations an “assault on minors”.

From Gay City News, New York

March 25, 2010

By Doug Ireland

The ruling dictatorship in Uzbekistan has jailed Maxim Popov, a 28-year-old psychologist and AIDS activist in the capital of Tashkent, for seven years for promoting homosexuality and thus corrupting minors through his HIV-prevention work. Popov’s jail sentence was also based on other charges stemming from his activism. With 28 million people, Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s most populous nation.

Popov was the founder of Izis, a Uzbek AIDS-fighting organization of young medical professionals and activists funded by UNICEF (the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund), the UK Department for International Development, Population Services International, a 40-year-old non-governmental organization, and other international groups.

Agence France-Press reported in a dispatch: “Authorities have long been suspicious that foreign aid organizations have been trying to spread homosexuality and drug use, said an activist who also requested anonymity. ‘I think they made Popov a scapegoat,’ he said.”

Popov was the author of “HIV and AIDS Today,” a brochure that discussed same-sex relations and the use of condoms in detail, sensitive topics in this culturally conservative, largely Muslim country, where public discussions of sexuality are prohibited and all media are tightly controlled by the dictatorship. All copies of Popov’s brochure, whose publication was funded by the Global AIDS Fund, were seized by authorities and burned, say accounts on a number of websites focused on Central Asia.

Popov’s charges revolved around the government’s contention that the book constituted an “assault on minors without violence” because of its candid comments about same-sex relations.

*****

According to a copy of the Popov verdict obtained by Eurasia.net, he was also convicted of distributing copies of “HIV and Men who have Sex with Men in Asia and the Pacific,” a publication of UNAIDS. “The content of this book, according to experts, is categorically mismatched with the mentality, moral foundations of society, religion, customs, and traditions of the people of Uzbekistan,” the verdict stated.

Consensual homosexuality between two men is a crime in Uzbekistan punishable by three years in prison. Criminal charges of homosexuality have been used in the past to silence critical journalists and human rights defenders.

In January of this year, the popular young journalist, poet, and radio broadcaster Khairullo Khamidov was arrested and jailed for belonging to a “banned social or religious group.” Khamidov’s broadcasts on a private radio station regularly dealt with such forbidden issues as homosexuality, prostitution, and corruption, mostly through his poems.

A short-lived newspaper that Khamidov founded and ran, Odamlar Orasida (Among the People), which achieved a circulation of 24,000 in only five months of publication, discussed the same issues, including homosexuality, and was closed in 2007 by authorities, according to a report earlier this year on the website of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty.

There is an obscure reference in the RFE/ RL report to the charges against Khamidov being related to his “personal life,” and some comments by Uzbeks on various other websites suggest that the “banned group” referred to by authorities in the charges against Khamidov was the homosexual community.

Because homosexuality is illegal, Uzbek police not only regularly harass gays but also subject them to extortion by detaining them and threatening them with prosecution, according to an article in China Daily.

AIDS activist Popov was arrested, tried, and jailed last year, but news of his prosecution and incarceration only began filtering out to the West since February 24, so tightly controlled is information by the dictatorship that Islam Karimov established in 1989 as ruler of the Uzbek Communist Party in the then-Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan.

The following year, as the Soviet Union was spiraling toward its 1991 dissolution, Karimov made himself the country’s president, and has been maintained in that post in subsequent sham elections where only candidates who support him are permitted to run for the nation’s parliament.

According to Reporters Without Borders, a Paris-based international group, the government blocks access to most of the independent websites that deal with Uzbek affairs.

Homophobic hate crimes are often perpetrated against those rare Uzbeks who dare to raise the issue of homosexuality in public. On February 17, three young men were convicted of murdering the prominent theater director Mark Vail, who was Jewish and of Russian origin, and whose family had moved to Uzbekistan in the 19th century. According to a dispatch from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), homophobia may have been the real motivation for the murder.

Vail, 55, who founded the Ilkhom Theatre in Tashkent in the mid-1970s and built it into a hub of Russian-language, Western-oriented culture there, died after being stabbed and brutally beaten last September 7 by the assailants near his apartment in the Uzbek capital. His attackers did not take any money or belongings.

One of Vail’s most successful recent productions was the play “White White Black Stork” about love between two religious school boys, based on a novel by the Uzbek dissident writer Abdulla Kadyri, who was executed during the Stalin era. Vail also staged another homoerotic play, “Taking Care of Pomegranate.”

The JTA dispatch reported that according to a leader in Tashkent’s Jewish population of 30,000, “many in the Jewish community there believed Vail’s murder was related to ‘White White Black Stork’ and its homosexual content.”

The homophobia-laden charges against AIDS activist Popov also included accusations of fiscal impropriety. But, according to a Facebook page set up by Popov’s friends, “The charges of fiscal impropriety come in the wake of years of harassment of NGOs [non-governmental organizations] by the Uzbek government via such measures as restricting or blocking access to foreign funds in bank accounts, repeated tax audits, and threatening visits from secret police or others urging NGO heads to close their organizations to avoid trouble.”

The UN says that Uzbekistan has one of the fastest-growing HIV infection rates in the world, according to the Associated Press.

A report about the Popov case posted on the Russian-based Central Asian news website Ferghana.ru, written in wobbly English and relying on one of its Uzbek readers, stated, “The attention to HIV/ AIDS problem in the republic is illustrated by the story of another reader: at one of the seminars, dedicated to this pressing issue, the representative of respected organization refused to put the condom on banana, arguing that the mentality of the nation must have been considered first. ‘It is sad to admit that all the official ministries think the same way. Perhaps, there are some best minds, but they have no voting power. There is no sex in Uzbekistan!’, says this reader.”

According to Eurasia.net, Izis, the AIDS group founded by Popov, has shut down since his jailing. The “Amnesty for Maxim Popov” Facebook page reports, “Popov kept Izis open even when the government blocked all access to funds, operating without pay and in collaboration with local community councils and volunteers. The climate in Uzbekistan makes it impossible for people within the country to speak out. Those of us who have worked with Maxim Popov know him to be a witty, humble, curious, enthusiastic, and effective educator and psychologist.”

The US news media have given no serious coverage to the Popov case. A Google search revealed only one sentence mentioning Popov in the New York Times, which appeared at the tail end of an Associated Press dispatch on the paper’s website; it inaccurately stated, “In late February, Uzbek activist Maxim Popov, who distributed brochures saying condoms and disposable syringes can help prevent HIV, was convicted of corrupting minors by promoting homosexuality, prostitution, and drug use.” In fact, Popov’s conviction dates from last year; it is only the case’s public reporting in the West that occurred in late February.

After 9/11, Uzbekistan became an important staging ground for US attacks against the Taliban in neighboring Afghanistan. As a result, the American government has soft-pedaled its criticisms of the country’s authoritarian regime and abhorrent human rights record. Popov and Izis have received funding from the US Agency for International Development, but a phone call to Robert O. Blake, the assistant secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs, seeking comment on the Popov case went unreturned as of press time. The “Amnesty for Maxim Popov” Facebook page is at facebook.com/group.php?gid=171801985748&ref=search&sid=528134066.2236888131..1&v=info.

Doug Ireland can be reached through his blog, Direland, at http://direland.typepad.com

(2)

Homosexual Activity is Illegal in Uzbekistan

From: Refworld

6 March 2007

Article 120 of the country’s criminal code punishes Besoqolbozlik, or “voluntary sexual intercourse of two male individuals,” with up to three years’ imprisonment. Sexual intercourse between two women is not mentioned in the code.

The London-based Gay Times online magazine states that Uzbekistan is a “deeply homophobic” country and that the rights of gay and lesbian Uzbeks are “poorly respected”. According to a 24 July 2003 China Daily article, gay Uzbek men interviewed by the newspaper indicated that homosexuals in Uzbekistan regularly experience police “harassment” and that gay establishments are “forced to close or [are] heavily monitored by police.” The men further noted that homosexuals are also subject to extortion by the police, who “routinely” detain them and “threaten them with prosecution.” (China Daily 24 July 2003).

A January 2006 World Organisation against Torture (Organisation mondiale contre la torture, OMCT) report on human rights violations in Uzbekistan states that “athough the crime of homosexuality]has a very high level of latency, law-enforcement bodies can use the charge in some fabricated cases to humiliate the accused or to blackmail homosexuals” In 2003, following a trial that Amnesty International (AI) describes as “unfair,” Uzbek journalist and human rights defender Surlan Sharipov was charged with homosexuality and sexual relations with a minor and sentenced to five and half years in jail. Although openly bisexual, Sharipov initially denied the charges and AI expressed concern that his confession was obtained “under duress”. In 2004, Sharipov was reportedly released from prison and subsequently immigrated to the United States, where he was granted asylum.

Homosexuality is reportedly rarely discussed in public in Uzbekistan. Homosexuality is one of several “forbidden” topics that journalists in Uzbekistan are discouraged from writing about.

According to Gay Times, there is “no gay scene as such” in Uzbekistan; however, in 1993, a gay rights group was established and, in 2000, a “gay community” web site was created.

Information on legal recourse and protection available to homosexuals who have been subject to ill-treatment could not be found among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate within the time constraints of this Response.

(This Response was prepared after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the Research Directorate within time constraints. This Response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim for refugee protection.)

(3)

The Uzbekistan Closet Carries On

August 2, 2007

By a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer 2003–2005

http://lgbrpcv.org/category/countries-of-service/uzbekistan/

We recently interviewed an RPCV who was in the last Peace Corps group to serve in Uzbekistan in Central Asia. Terrorist incidents and worsening relations between the U.S. and Uzbek governments over human rights and other issues caused Peace Corps to evacuate all PCVs in 2005 and close down PC programs. This RPCV has asked to remain anonymous. He will explain why later in the interview.

Q. How did you come to join the Peace Corps?

During my senior year at college, I had toyed with the idea of joining the Peace Corps after meeting with a PC recruiter. Never in my wildest had I ever planned on this. I really did not have much ESL or TEFL experience, but once my recruiter saw that I was willing to teach English in Central Asia, she signed me right up. I thought it would be interesting and with my language and cultural skills, I thought it would be a match. I did discuss my sexuality with the recruiter, but neither of us thought that it would hamper my service in the Central Asia. So after only four months after applying, I left for my assignment in August of 2003.

Q. What concerns did you have about being a gay PCV in Uzbekistan, a conservative Muslim country?

I had read just about everything there was out there for future gay PCV’s in a Muslim country. My recruiter helped put my mind to ease that I would be ok and that if I felt uncomfortable during my service, PC would be there to help me. I assumed that I would not come into contact with another gay person during the two years I would be in Uzbekistan. I guess I really didn’t think much about leaving a pretty comfortable life here in the US and living in a Muslim country. I was just so excited to be going, I didn’t think about it. What did I have to lose?

Q. How did you find out about Uzbek attitudes towards homosexuality once you got to there?

Once I arrived there I was shocked to discover that there were about 10 other gay guys already in-country from earlier PC groups. Although I was the only out volunteer in my group, having these other folks there to talk with was assuring. PC Uzbekistan had even set up a mentor program pairing me with another gay guy who had already been there for a year. We actually ended up dating for a while. That relationship became my security and helped me through those first few months.

I learned about the attitudes towards homosexuality in Uzbekistan mostly from these other volunteers. I never actually discussed homosexuality with Uzbek friends, but I did learn about their views from passing comments and conversations between my host families and friends. I did not tell them I was gay.

Q. Tell us about your teaching assignment(s) once you got to Uzbekistan. How were they different than other PC assignments?

Once I arrived in Uzbekistan, my fellow volunteers and I were put through rigorous assessments before our placement was determined. I was assigned to teach in an Islamic madrassa (religious secondary-university school). This was the first time that PC had ever placed a volunteer in a religious affiliated assignment in Uzbekistan. Since I had experience with the Muslim culture and had an Arab family background, PC staff determined this would be a good fit. We never discussed the fact of how my being gay would play out in this scenario. I left my personal life at the door of the madrassa every day. When I was asked questions about why I wasn’t married, I had to make up a convincing story.

Q. Although you left before PC was evacuated from Uzbekistan what did you later find out what happened during that time?

I had been home awhile when I learned that PC Uzbekistan was actually going to be evacuated and the volunteers sent home.

My RPCV friends were evacuated to the US, and I went to visit them the day they arrived to help console them. I think that many of them were happy to see a welcoming face, but I could see the pain and confusion in their eyes after having so abruptly left their lives in Uzbekistan. On one hand, I was sad that I had made the decision to leave early. On the other hand, I was happy that I had met with closure in Uzbekistan before I left, unlike my friends who had been uprooted from their host families and work.

Q. Are you still in touch with friends and colleagues you worked with in Uzbekistan?

Yes, I still have some friends in Uzbekistan, but not many. On my most recent trip back to Uzbekistan (for my current job), I met with some of my host family members and visited my school. Most people I knew though have left for better jobs in Russia or Europe. I missed the good work PC had done there. Most of my close Uzbek friends are now here in the States studying.

Q. Because you are still in contact with many Uzbek friends, you’ve decided to remain closeted with them. What has led to your decision?

Staying closeted with my close Uzbek friends here in the States has been difficult. There are times when I would like to just yell out to them that I am gay. For the time I was in Uzbekistan, these people became like my family and actually were my support system. Coming out to them would be like coming out to my own family in the States all over again. This will take some courage but over time I feel it will happen. In fact, I am sure that some these friends now living here have their suspicions.

Q. Do you think about being more open with some of them in the future if you’re going to continue these relationships?

Yes indeed. I would love to tell them and have them welcome me with open arms much as they did when I first arrived in Uzbekistan. I was welcomed there like a long lost family member. Being gay, would not necessarily change that with my closest friends.

I feel that once my friends from Uzbekistan have experienced my culture, similar to how I experienced theirs, we’ll both come to a level of comfort and be totally open with each other. One day I’ll have the courage to tell them face to face, and not in a letter or an email. After all, it is one of the main goals of Peace Corps service to exchange cultures. I feel that being a gay volunteer leaves one with quite a unique experience, like no other volunteer will encounter. I would like to share that with them.